***This post is the sixth in a series of eight weekly exercises designed to take our short stories from rough draft to finished "masterpiece"(or as close as we can get ;-) with the help of the late John Gardner and a host of other well-known authors and teachers. Click here for Part I ***

“Vivid detail is the life blood of fiction…” – John Gardner

I am so behind on my revisions for this story! This most recent pass-through (the one with a focus on dialogue and subtext) took much longer to complete than I expected. Even though my story has just five or six partially dramatized scenes --and even fewer passages of dialogue--it took quite some time to hone that dialogue down to only the most meaningful and significant lines. Now it’s time to move on to the next revision pass: authenticating detail and description.

So what does our mentor, the late John Gardner, have to say about detail?

The details in this brief passage from Colm Tóibín’s short story “The Use of Reason” capture only a tiny aspect of who this mother is, but the few, carefully chosen words and details suggest so much more beneath the surface:

“Good authenticating details set a trap that captures a small piece, a tiny aspect, of what’s being described in a way that allows the reader to come to understand what’s being described for himself,” says Dave Koch, author of one of the clearest explanations I’ve read on the subject of authenticating detail. “[Readers] of literary fiction want to be able to figure things out for themselves; they want to do work. When a story allows you to do this sort of work—to come to your own decision, to come to your own conclusions—you participate in that story. And that sense of feeling like you participated, like your opinions and interpretations matter, is a big part of the pleasure you take from reading literary fiction.” Koch gives us five steps to follow to help make our readers feel like they know just enough about a character or place (or whatever it is you’re trying to describe). To get the whole scoop including some good examples, read the rest of Dave’s article here, on the Gotham Writers’ Workshop site. The five steps:

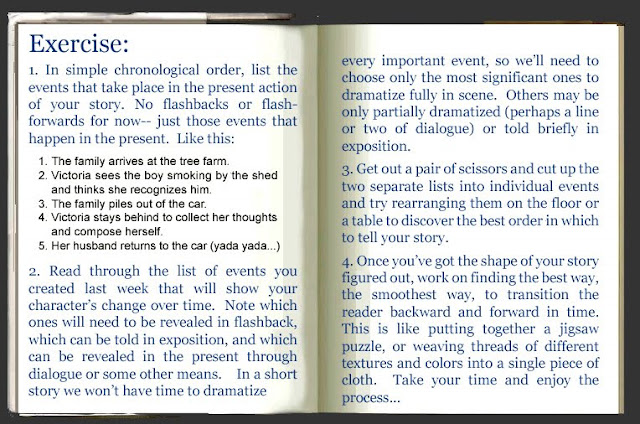

- Make the decision to capture whatever it is you’re trying to describe. Set a trap.

- Identify details you don’t need for this capturing. Ordinary details are your enemy.

- Look to unusual details to capture the big picture. Unusual details let readers do work.

- Lie, cheat, and steal. Do whatever you have to. You don’t necessarily capture the truth by being truthful.

- Trust the reader. Don’t explain something after you’ve captured it. “Over-explaining takes all the power away from [the] authenticating detail. Avoid that by letting the reader figure things out for himself.”

Author, Monica Wood, interviewed for The Glimmer Train Guide to Writing Fiction: Building Blocks (a wonderful resource for both inspiration and technique) talks about the importance of picking just the right detail when describing something-- a place or character, for instance:

I’m excited to discover that in addition to her novels and short stories Monica has written a number of books on the craft of writing, one of which is Description, a book in the popular “Elements of Fiction Writing” series. I’m looking forward to checking that one out.

John Gardner: The Art of Fiction

Dave Koch: "Authenticating Detail" Gotham Writers' Workshop (article first appeared in "The Writer" magazine)

Monica Wood: interviewed for The Glimmer Train Guide to Writing Fiction: Building Blocks

Colm Tóibín: "The Use of Reason" in the collection Mothers and Sons