Last week we worked on how to convince the reader that there's a good possibility our protagonists might change their ways by the end of our stories--even if they don’t end up changing at all. If nothing else we’ve at least shown that they’re capable of change, thereby keeping the reader in suspense until the end of the story. And for those of us whose protagonists do change, we’ve come up with a list of incidents designed to convince our readers that the character’s change is not only plausible but, in hindsight, inevitable. Surprising, but inevitable… that’s the key.

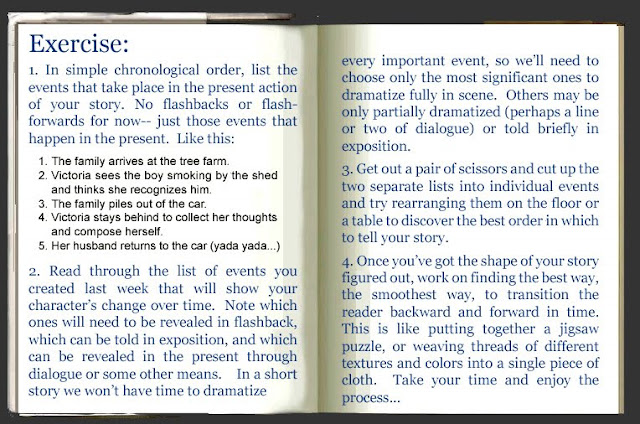

I don’t know about you, but when I came up with my list of incidents it became apparent that many of them will need to be shown in flashback (or flash-forward), or another way entirely, but in any instance they’ll likely throw my story events out of chronological order. So figuring out the best way, the smoothest way, to sequence and transition those events will be crucial.

When American author Lan Samantha Chang wanted to tell stories based on the lives of her parents and the era in which they grew up in China she realized that, though set in the present, she would need to move backward in time to find the heart of the story, to uncover “the mystery of the past.” In her excellent essay, “Time and Order: The Art of Sequencing,” Chang (currently director of the prestigious University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop) writes that “Every story shapes a pattern in time, and its writer must find that shape…. Manipulating sequence can greatly increase a writer’s range, her flexibility and her authority. A leap backward can dazzle the reader and develop his understanding of the characters. A complex story may move back and forth in time, creating a spellbinding pattern. A subtle, chronological telling can draw the reader smoothly into the author’s world, holding him rapt with an awareness of its possibilities.”

Though certainly not as popular in today’s stories as the flashback, much can be gained from the flash-forward, by taking the reader briefly forward in time. Says Chang: “[The flash-forward] can provide us with a startling and revealing vision of the characters’ futures as their present conflicts unfold, helping us understand the present story in a larger context.”

In the first pages of his novel, Giovanni’s Room, author James Baldwin propels the reader forward to the events of a morning that has yet to take place. We learn that the protagonist’s lover is to be guillotined that day and that the protagonist blames himself for what has brought the two of them to this awful place in their lives. The opening, a flash-forward, sets the mood for the novel, and we feel that sense of destiny and significance as we watch, through flashback, the characters meet and fall in love. The opening of Giovanni's Room:

In another piece by James Baldwin, the short story “Sonny’s Blues,” the narrator (an algebra teacher) wants his younger brother Sonny, a musician and a recovering drug addict, to have a normal, “safe” life, away from his old friends and his nightclub music, the jazz that Sonny loves. The author employs a series of significant flashbacks, some dramatized, some expository, to show the narrator’s change over time. The transition that thrusts the reader into the past begins at an awkward (for the narrator) family dinner with his wife and Sonny, (their parents are long dead) and hinges on the narrator’s thoughts, his desire to keep his brother “safe”:

In another piece by James Baldwin, the short story “Sonny’s Blues,” the narrator (an algebra teacher) wants his younger brother Sonny, a musician and a recovering drug addict, to have a normal, “safe” life, away from his old friends and his nightclub music, the jazz that Sonny loves. The author employs a series of significant flashbacks, some dramatized, some expository, to show the narrator’s change over time. The transition that thrusts the reader into the past begins at an awkward (for the narrator) family dinner with his wife and Sonny, (their parents are long dead) and hinges on the narrator’s thoughts, his desire to keep his brother “safe”:

Suddenly, without even realizing it, we find ourselves transported back to the narrator’s young adulthood in Harlem, to the early relationships with his parents, his brother, and others, until eventually we come full circle and return to the present, moving on from there. Each stop along this seamless journey through the past is a significant one. Each event the author chooses to show us not only propels the story forward, but peels back the layers in those early relationships revealing the narrator’s failed attempts at understanding and helping his troubled brother. Through these past incidents Baldwin convinces us that the narrator’s change when it comes is not only plausible, but genuine.

With any sudden shift in time, be it forward or backward, the key of course is to do it without jarring the reader out of the fictional dream you’ve worked so hard to create. Sol Stein (editor, creative writing instructor, and author of nine novels) says “The reason flashbacks create a problem for readers is that they break the reading experience. The reader is intent on what happens next. Flashbacks, unless expertly handled, pull the reader out of the story to tell him what happened earlier. If the reader is conscious of moving back in time, especially if what happened in the past is told rather than shown, the engrossed reader is reluctant to be pulled out of his reverie to receive information. If we are enthralled, we don’t want to be interrupted. Therefore, the art of writing flashbacks is to avoid interrupting the reader’s experience. I’ll show you how it’s done.” … which indeed he goes on to do in Stein on Writing, his fabulous book on craft. Stein gives great practical advice in all areas of craft, with an entire chapter devoted to flashbacks and how and when to use them. Stein’s books differ from many other books on writing in that his focus is always and foremost on the experience of the reader.

Lan Samantha Chang: "Time and Order: The Art of Sequencing,"from Creating Fiction (edited by Julie Checkoway)

Sol Stein: Stein on WritingLan Samantha Chang: "Time and Order: The Art of Sequencing,"from Creating Fiction (edited by Julie Checkoway)

James Baldwin: Giovanni's Room

James Baldwin: "Sonny's Blues" from his collection of short stories titled Going To Meet The Man

Part I: Introduction

Part II: Setting & Emotion

Part III: Character Motivation & Change

Part IV: Story Shape

Part V: Dialogue

Part VI: Authenticating Detail & Description

Part VII: Tension & Reader Anticipation

Part VIII: Plot

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for sharing your thoughts...